NSW Historical Perspectives

In a Navy Training Plan (NTP) developed the 1970s in parallel with major Naval Special Warfare development programs, it was envisioned that each UDT and SEAL Team would be outfitted with SDV (SEAL Delivery Vehicles; previously Swimmer Deliver Vehicles) capabilities. In due course, however, it was realized that SDVs were extremely maintenance intensive, and that the skills necessary to pilot and navigate these sophisticated platforms were not just unique, but extraordinary. For several years the Mk VII SDV had been delivered to all of the UDT and SEAL teams, but some simply let them sit idle, because they didn’t have the training time or manpower to establish operational or maintenance capabilities.

With the planned reestablishment of UDT-22 at NAB, Little Creek, Virginia in 1979 it was decided to organize the command as fully functional team dedicated solely to the operation and maintenance of the SDVs; and, over the ensuing years, this was accomplished very effectively. This closely coincided with the pending introduction of the advanced-technology Mk VIII and Mk IX SDVs and the first submarine Dry Deck Shelter (DDS) to transport SDVs.

When the UDTs were reorganized as SEAL Teams in 1983, UDT-12 and UDT-22 were officially established as SDV Teams ONE and TWO respectively. Within 12-18 months, both teams began deploying SDVs operationally. SDV Team ONE had the advantage of the submarine USS Grayback (APSS-574) to provide tactical mobility. Grayback had been converted in 1958 into a guided-missile submarine armed with Regulus nuclear-cruise missiles. In 1968, the Navy finalized conversion of the ship to accomplish UDT, SEAL, and other special operations capabilities. It’s sister ship, USS Growler, intended for east coast operations, was not modified, because its funding was reprogramed to complete Grayback’s conversion. In 1982, USS Cavalla (SSN-684), a 637 Class fast-attack submarine, completed modifications to replace Grayback. Additional 637 Class submarines would continue to be modified.

SDV programs were managed out of the Naval Special Warfare Program Office (SEA 06Z) at the Naval Sea Systems Command in Washington, DC by a SEAL officer. It would take several years for the Mk VIII and Mk IXs SDVs to phase-replace the Mk VIIs. This was because the new SDVs were assembled one at a time at the Navy Laboratory in Panama City, Florida, and not mass produced. The focused SDV “build” program at Panama City was unique, and a comprehensive SDV support organization was established without which the SDV Teams might have floundered. The dedicated Panama City engineering and support staff also created the means to continually upgrade SDV operating capabilities through a continuous life-cycle experimentation and modernization program.

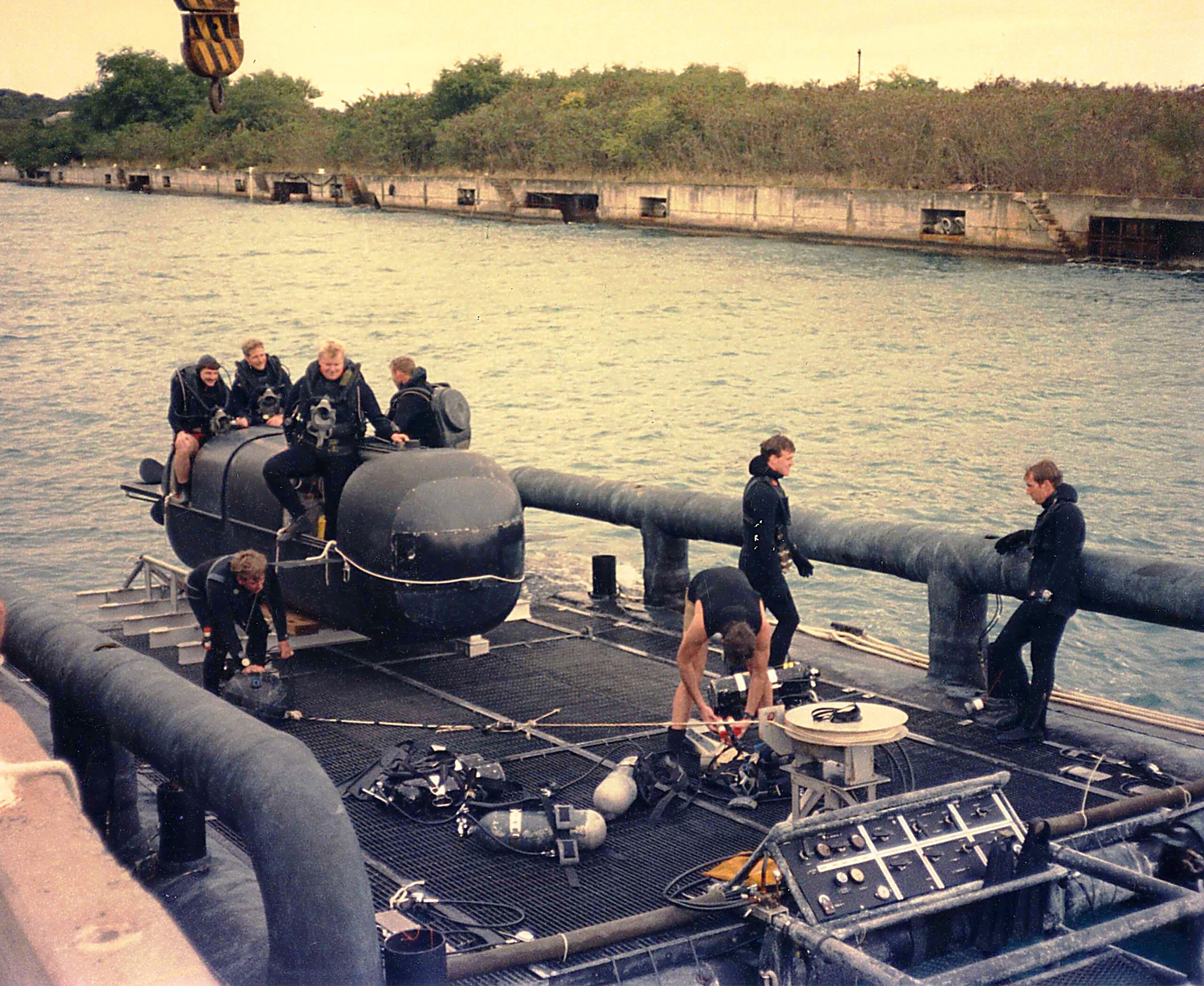

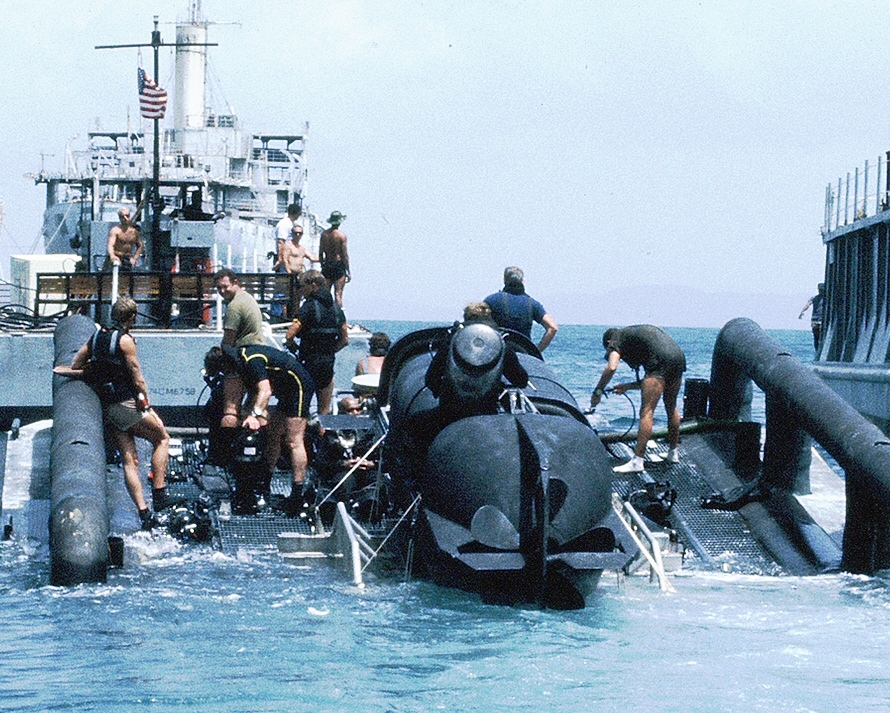

SDV Towing Sled

When you can’t get a submarine for support, what can you do? The east coast had considerable difficulty finding operational mobility platforms for the SDVs, and was largely relegated to deployments on amphibious ships. This created opportunity for creativity and innovation. One solution was SDV towing sleds, which were fabricated to assist launching and recovering SDVs from the high freeboard of amphibious ships.

These sleds were quite ingenious, since at idle speed they would sink on pontoon floats; allowing the sled to remain just below the surface of the water. The SDV could then easily maneuver in and out of the floating sled; and, when secured, could be towed by a high-speed support craft. The forward speed of the boat would cause the sled and the SDV to drain residual water and allow the sled to get upon surface plane for transit. The sled could increase the tactical range of an SDV mission by getting the SDV and crew closer to targets afloat or ashore using their own life support and SDV battery power.

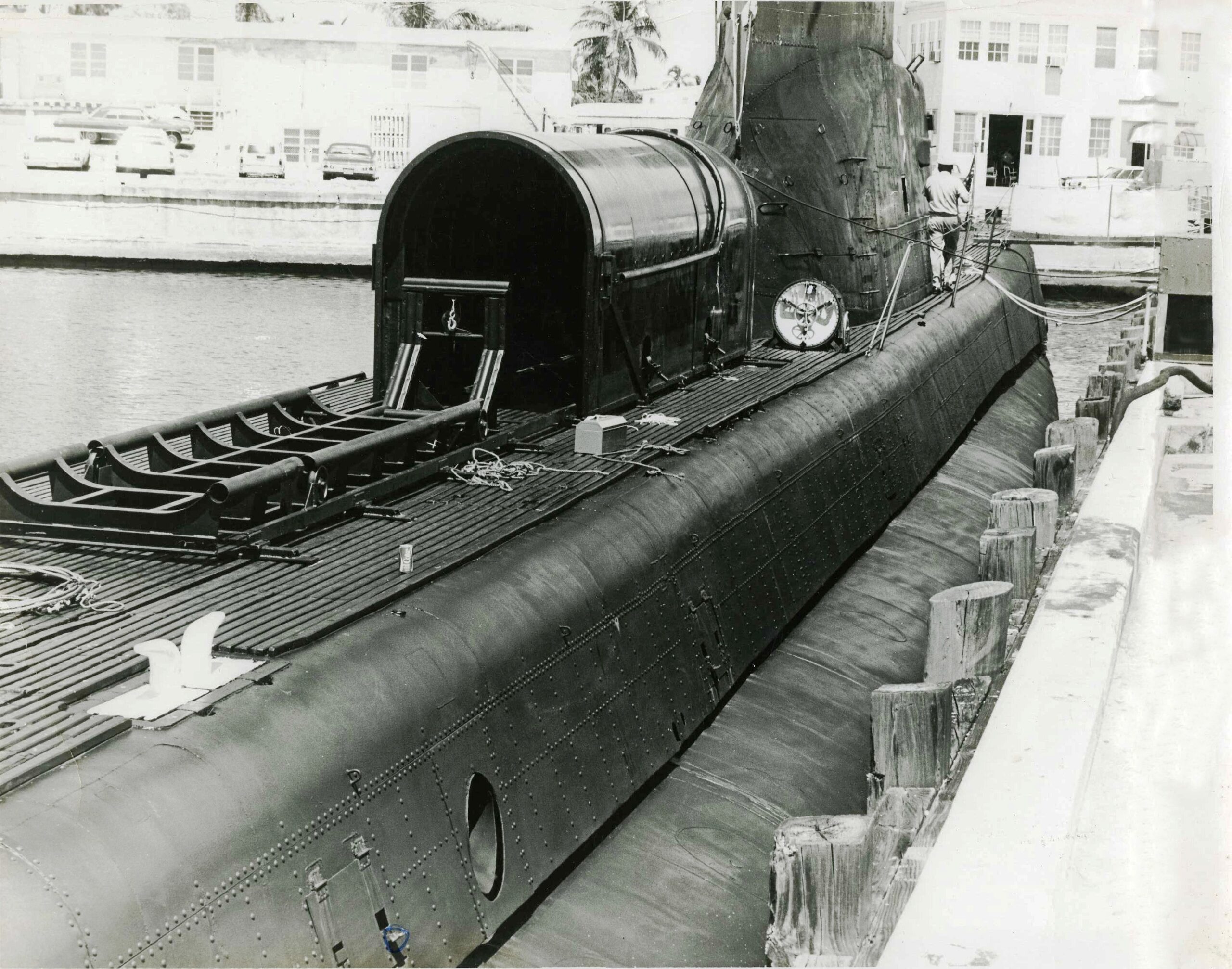

SDV Wet-Deck Shelter

Because USS Growler was not converted for use on the east coast, the men fashioned the concept of a “wet” deck shelter to be used on conventional submarines in the Atlantic. One shelter was fabricated and delivered. It was designed to accommodate either a MK VII or Mk VIII SDV with bow planes removed. The shelter and its cradle and track system were bolted to the superstructure of the host submarine. This shelter was used only once for at-sea training, and was never deployed operationally.

Complex scheduling of submarines prevented routine use of the shelter, and it was not something that could be used to deploy overseas with an SDV embarked. To do so would restrict the submarine’s capability to deep dive; restricted by the SDV’s design depth. Also, the SDV would have been harmfully exposed to salt water during prolonged submerged operational periods, thus, difficult to maintain – battery charging for example.

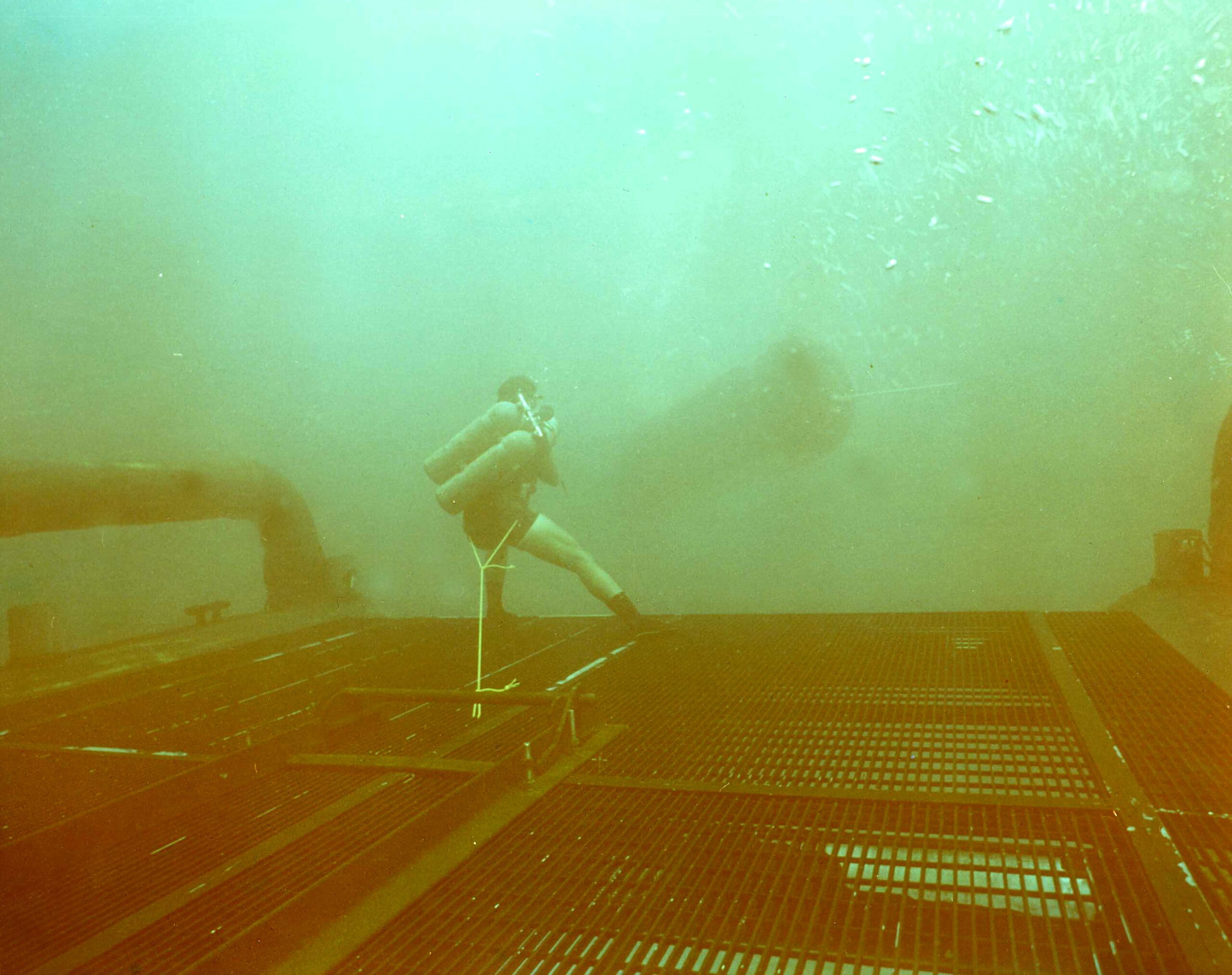

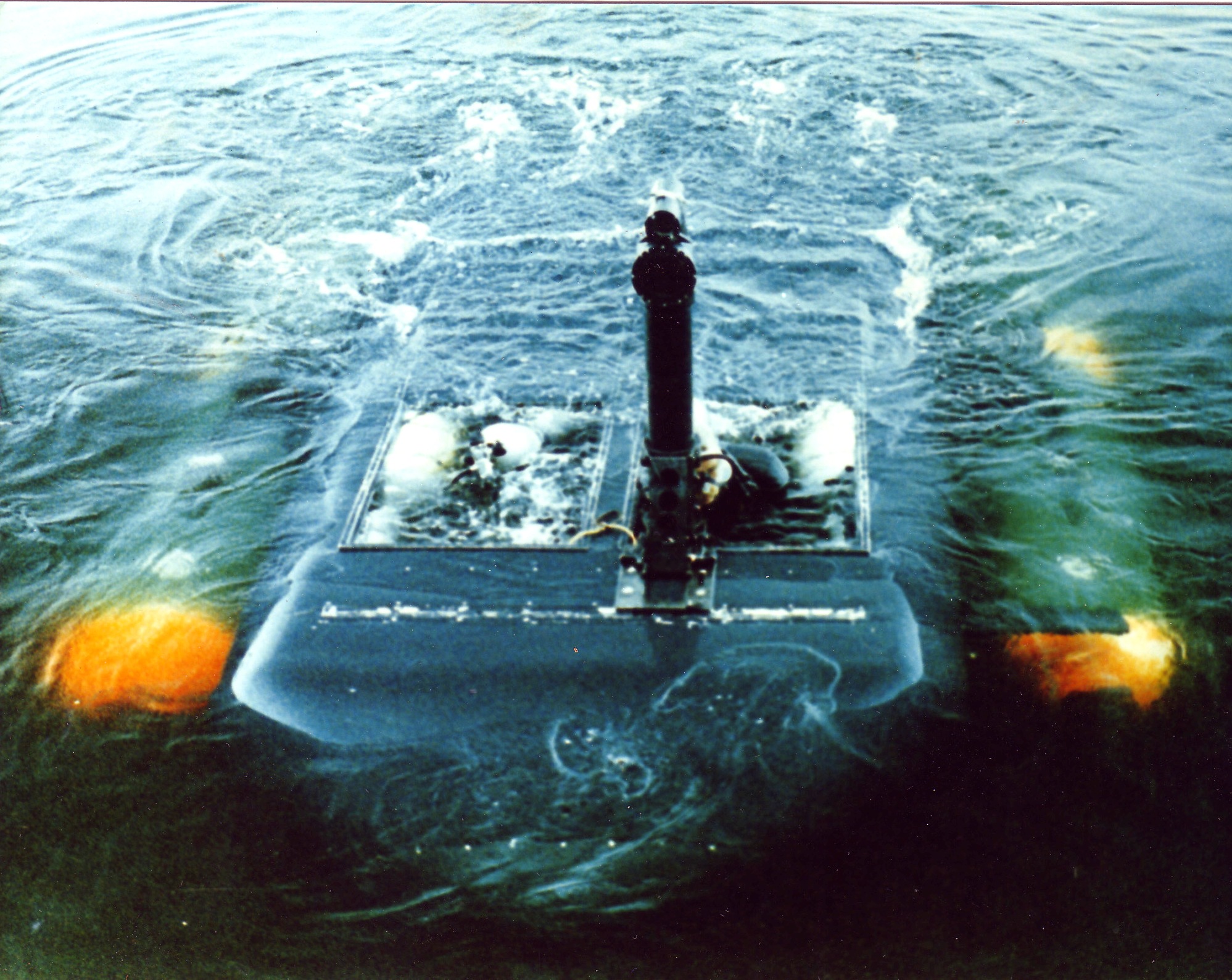

Submarine Training Platform

Because submarines services in general were difficult to obtain for underway training, a submersible training platform or SUBTRAP was fabricated. With a variable ballast system, SUBTRAP was towed by a surface vessel and designed to portray the deck of an underway submarine. The training device was operated and maintained by the SDV Teams. Although quite innovative, they were very maintenance intensive and rarely used. Moreover, they took SDV operators and technicians away from their primary jobs, and the SDV Teams were already undermanned.

Standoff Weapons Assembly

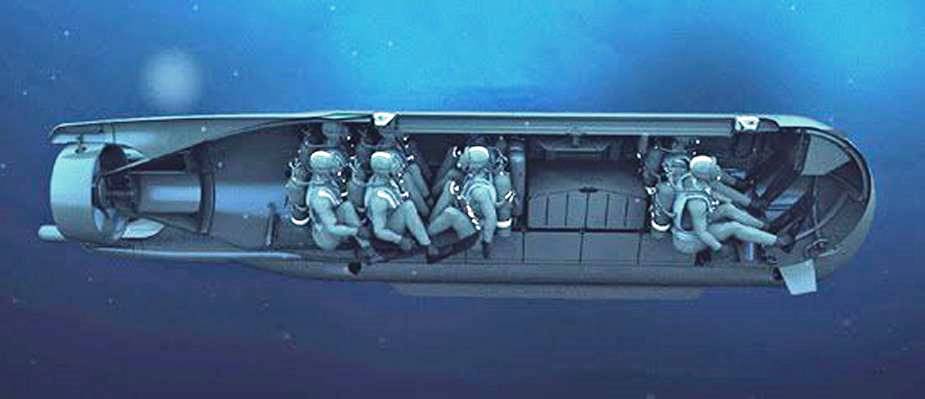

It was outlined earlier that the Mk VIII SDV was designed for personnel and weapons delivery. It could carry six fully equipped divers or two or three divers and weapons. These weapons included the complete inventory of limpet mines and a family of demolition charges. The Mk IX SDV, which was a low-profile design, was intended primarily for reconnaissance missions, but it also had a cargo compartment that could carry weapons. The pilot and navigator lay inside the MK IX SDV in a prone position. Under TDP 38-01, the Swimmer Weapons System developmental program, a special weapon was designed exclusively for the MK IX SDV. It was called the Standoff Weapons Assembly or SWA.

The SWA was a modified U.S. Navy Mk 37 torpedo. This torpedo had electric propulsion and didn’t need to be ejected out of a torpedo tube with compressed air like older torpedoes. This made it ideal for SDV use. For a long time, the Mk 37 was the primary U.S. submarine-launched torpedo. It was replaced by the Mark 48 torpedo beginning in 1972. As a result, many MK 37s remained in the Navy inventory and were readily available for use.

Among the largest technical challenge in modifying the Mk 37 torpedo for the Mk IX SDV was its unique “swing-arm assembly,” a launcher-rail system for integration with the submarine Dry Deck Shelter (DDS). The SDV and weapons were required to fit inside the DDS and also confirm to sub-safe regulations. The only way to do this was to hard mount the SWAs inside the DDS. Once the DDS was flooded, the SWAs became near neutrally buoyant, and could be taken from their mounts and attached to the swing-arms. Once outside the DDS, the torpedoes would be “swung down” and locked into position for SDV transit and launch.

Another major technical problem involved the actual launch system. The SWA was aimed using a periscope encompassing a stadimeter (cross hairs in the lens). Once prepared for launch, it could be fired only after its gyro-compass had stabilized, which didn’t take a long time. The aiming and firing took some skill, since the SDV on the surface was prone to rocking motions created by the environmental conditions. The weapon was fired when range and bearing of the target was determined. The weapon would be fired when the target was centered in the cross hairs of the stadimeter. Targets were assumed to be stationary in anchorages or at pier side. Safety was built into the SWA, since it could not arm itself until it travelled a distance of 750 yards. The SWA capability completed successful operational evaluation and was being prepared for fleet service. Because of cost considerations, however, the Mk IX SDVs were instead removed from the SDV Team inventory, and the SWA capability went with it. The SWAs were not compatible with the Mk VIII SDV.

Little Bo Peep

Before the Mk IX SDVs were eliminated from the active inventory, the men at SDV Team TWO developed a concept that they called the “Little Bo Peep” weapons-delivery configuration. This involved carrying limpet-mines on the SWA swing arms. The concept was never taken beyond the SDV Team, since the MK IX would not be available. Moreover, it would have involved a lengthy and expensive weapons-safety review and approval process, but this concept demonstrated the traditional and never-ending innovative thinking of the men.

And, for those young enough to not know or remember “Little Bo Peep,” the name derives from the title of a children’s poem of the same name by Mother Goose. The first line of the poem goes: “Little Bo-Peep has lost her sheep.” The weapon to be carried on the swing arms was called the Limpet, Modular, Assembly or LAM, thus, sheep was juxtaposed to lamb, and the pseudo name Little Bo-Peep for the capability – Ah, Frogman Wit!

The Mk VIII SDV remained the workhorse submersible throughout the 1980’s and into the early 1990’s, when a complete modernization program was initiated. This resulted in a new SDV with substantially more capable and efficient propulsion, navigation, sonar, and electronic subsystems. This resulted in the fielding of the MK 11 Shallow Water Combatant Submersible (SWCS).

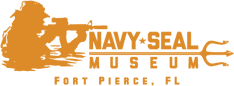

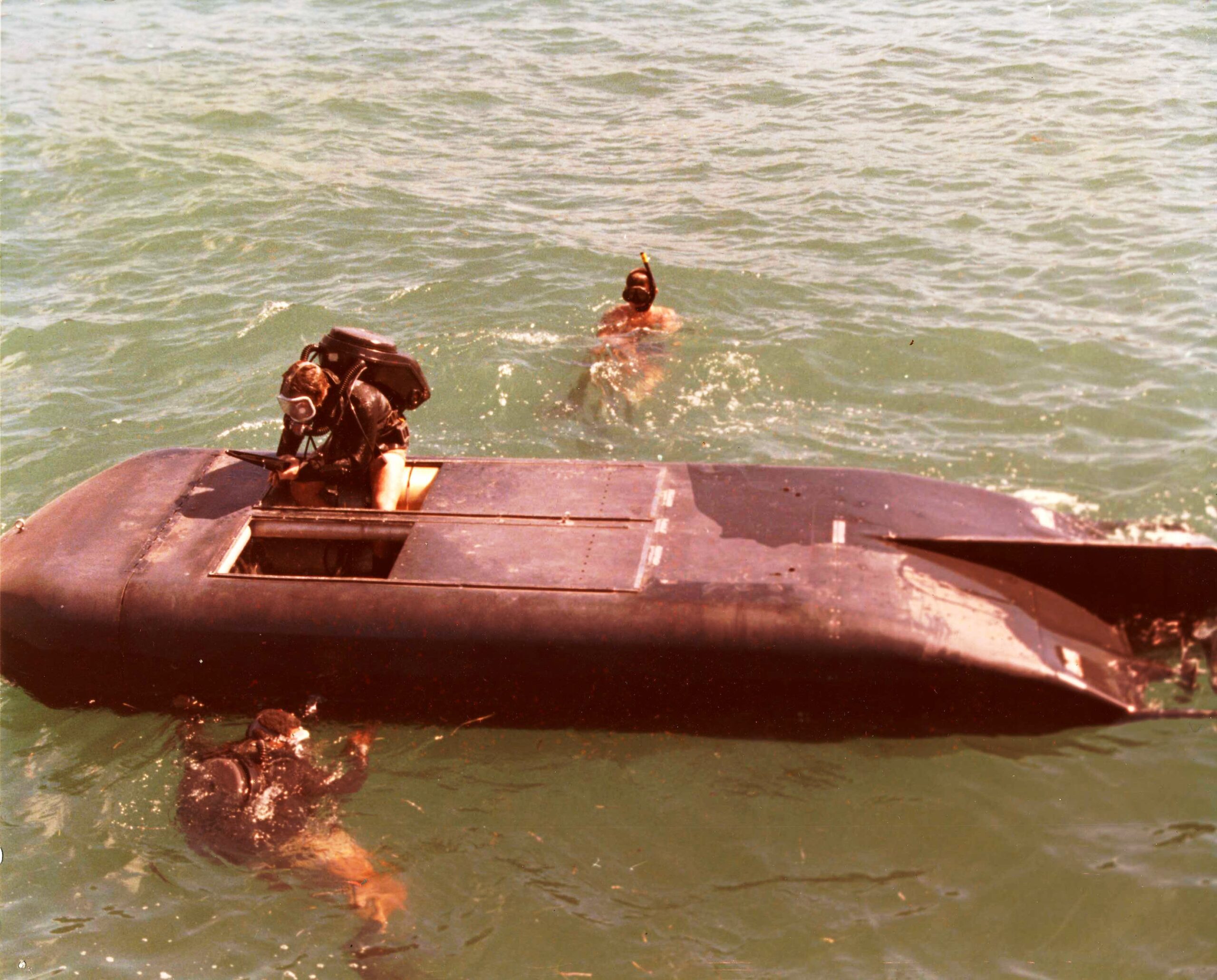

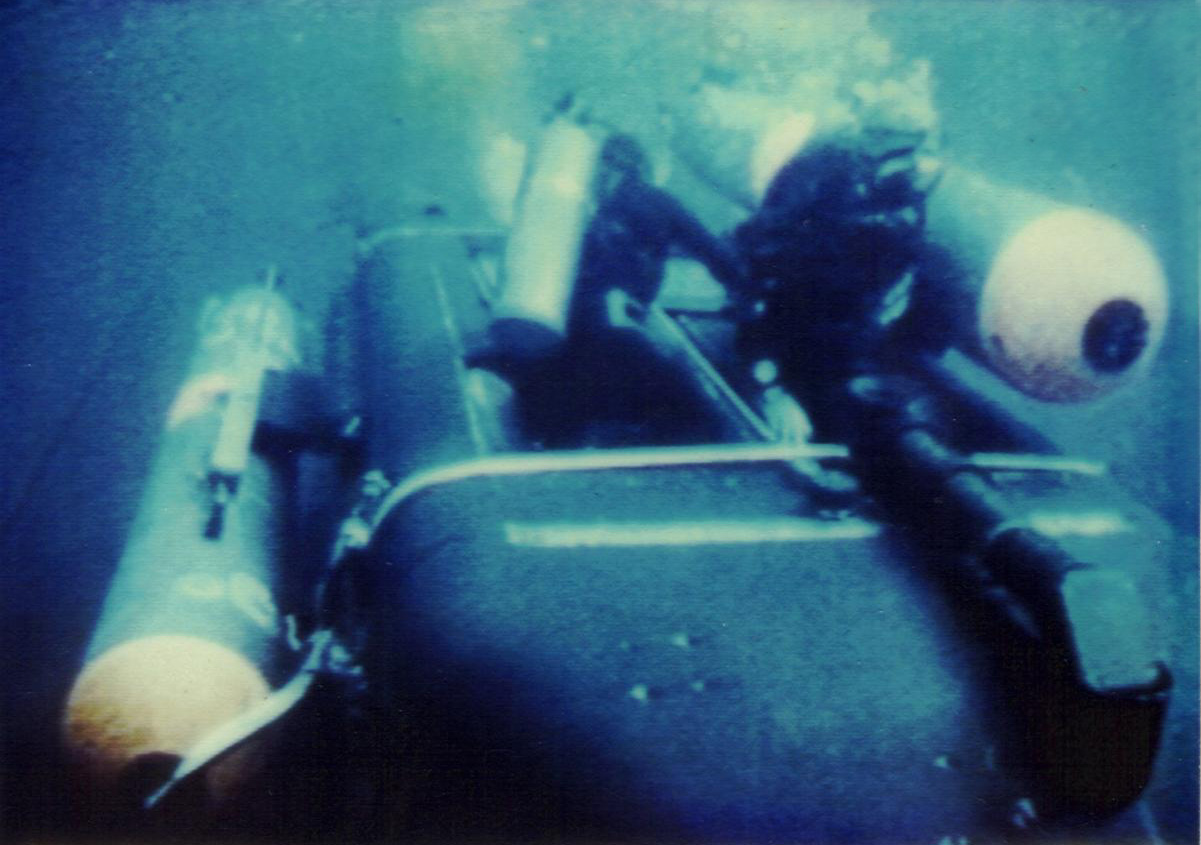

November 1967: Four divers are embarked in an underway MK VII, Mod 0 SDV. Photo was taken from the surface safety boat

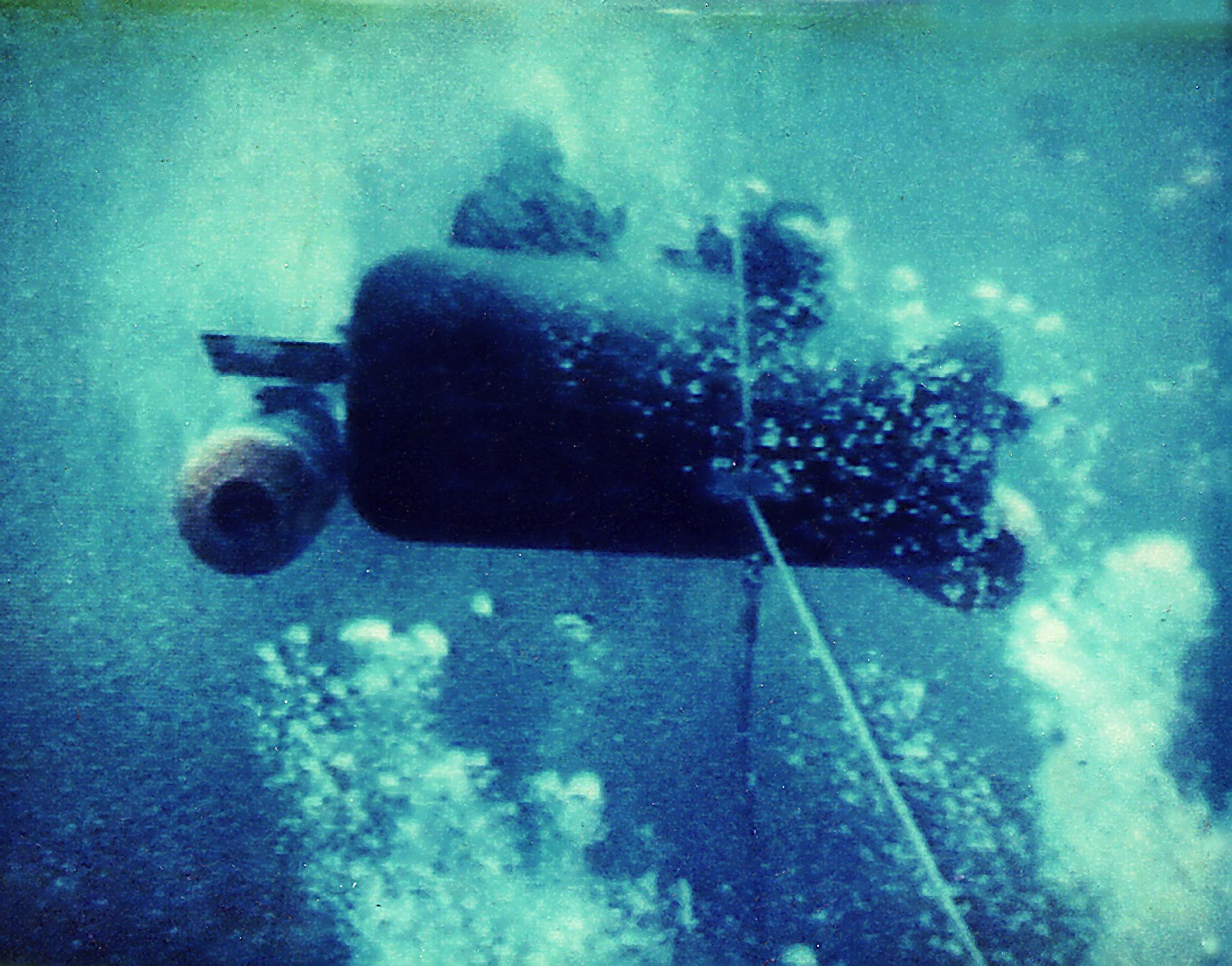

MK VII, Mod 5 SDV underway

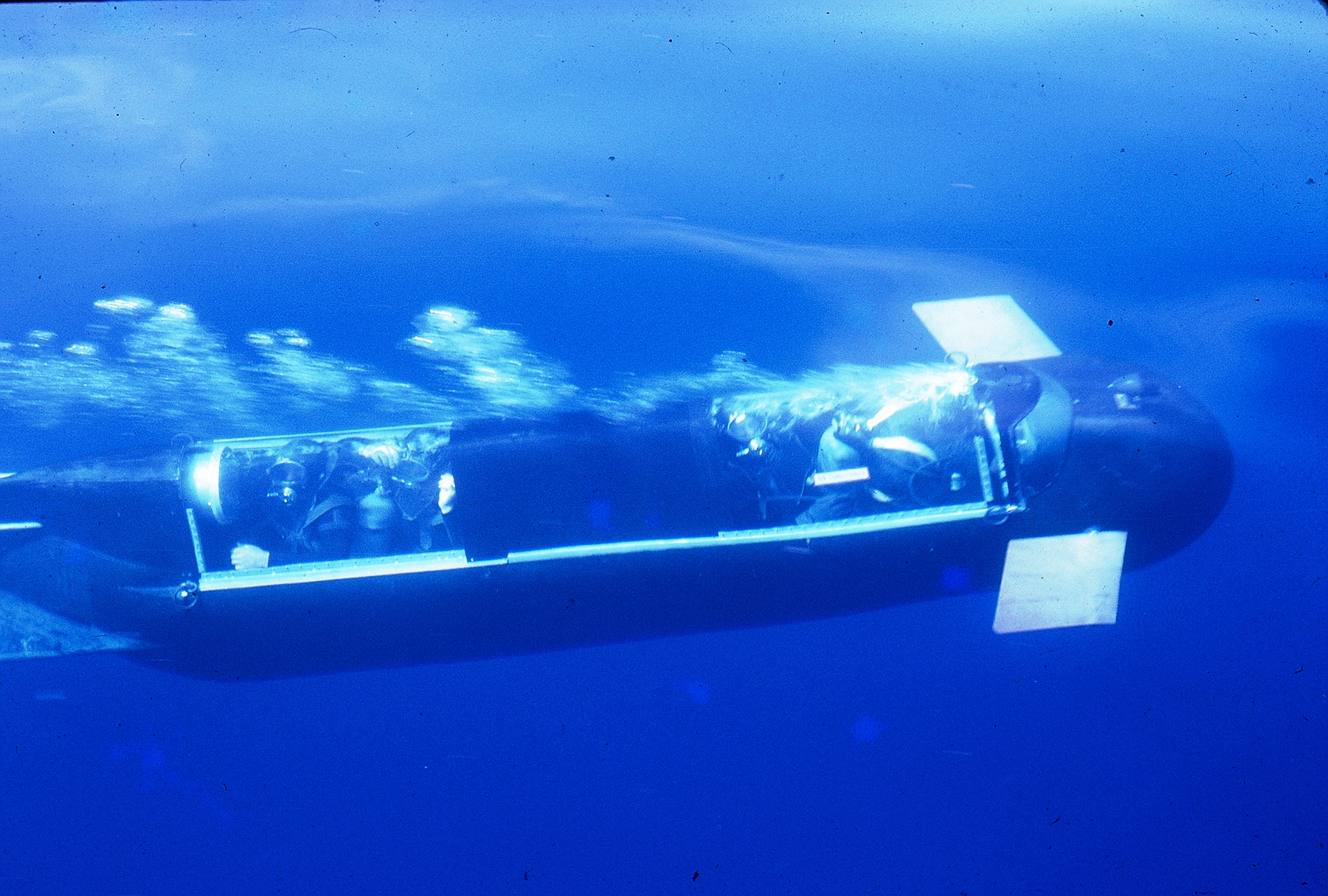

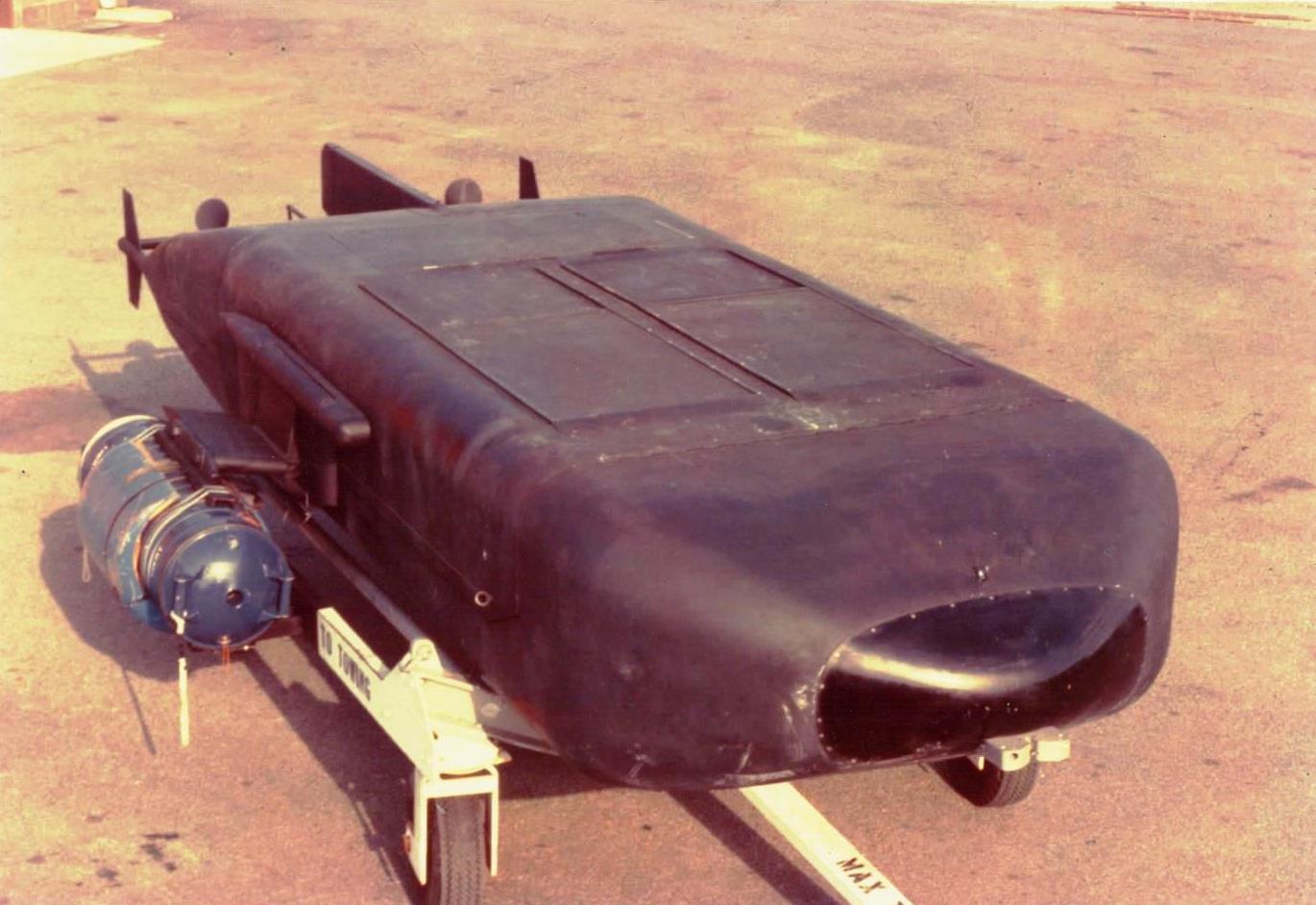

MK VIII SDV draining water while being sling lifted after a training operation.

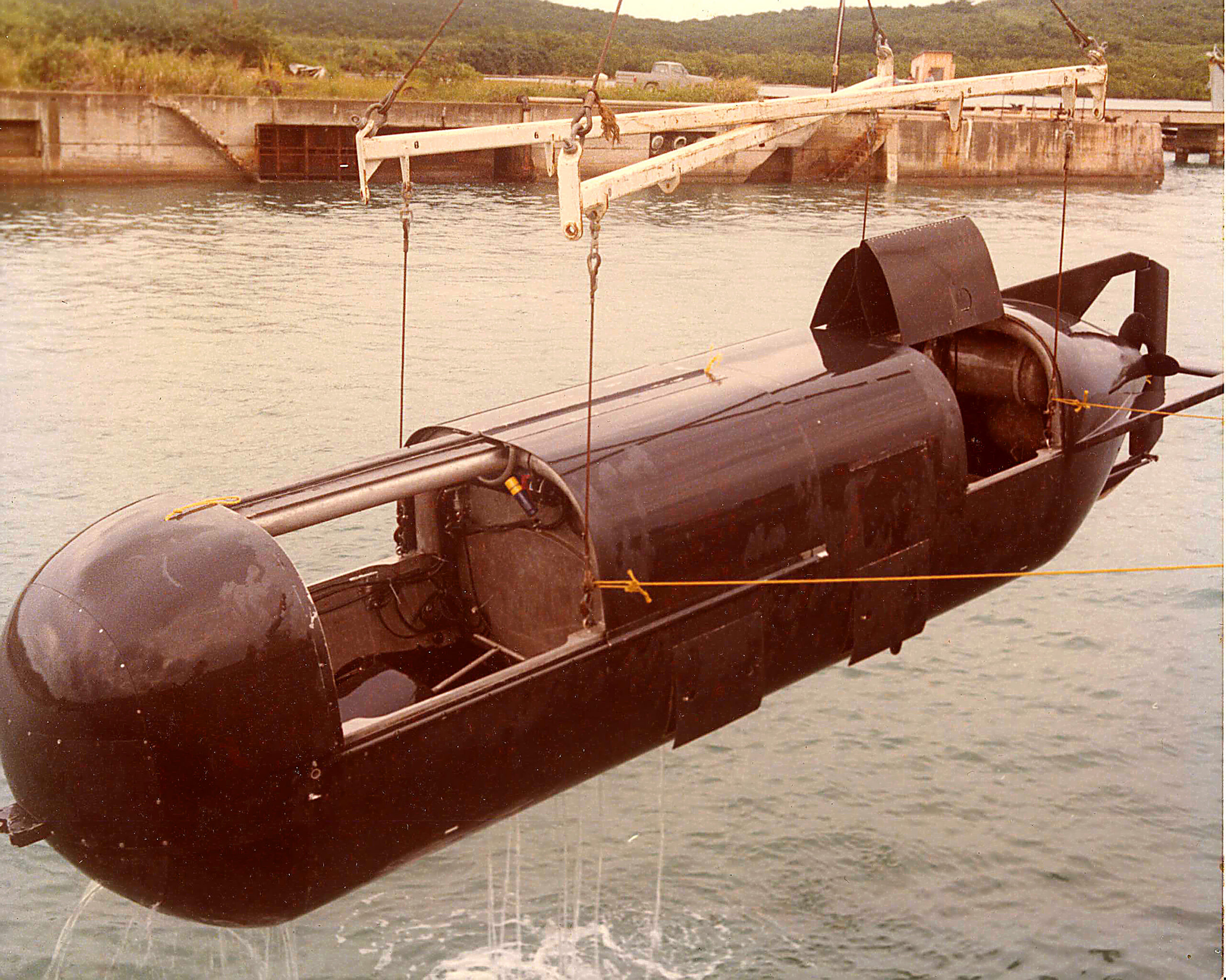

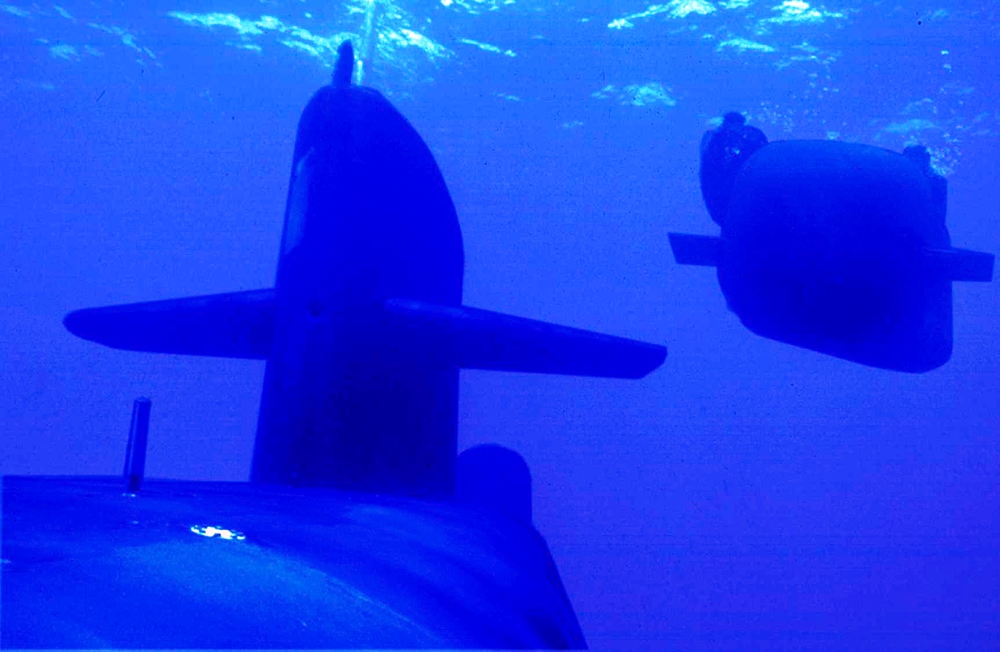

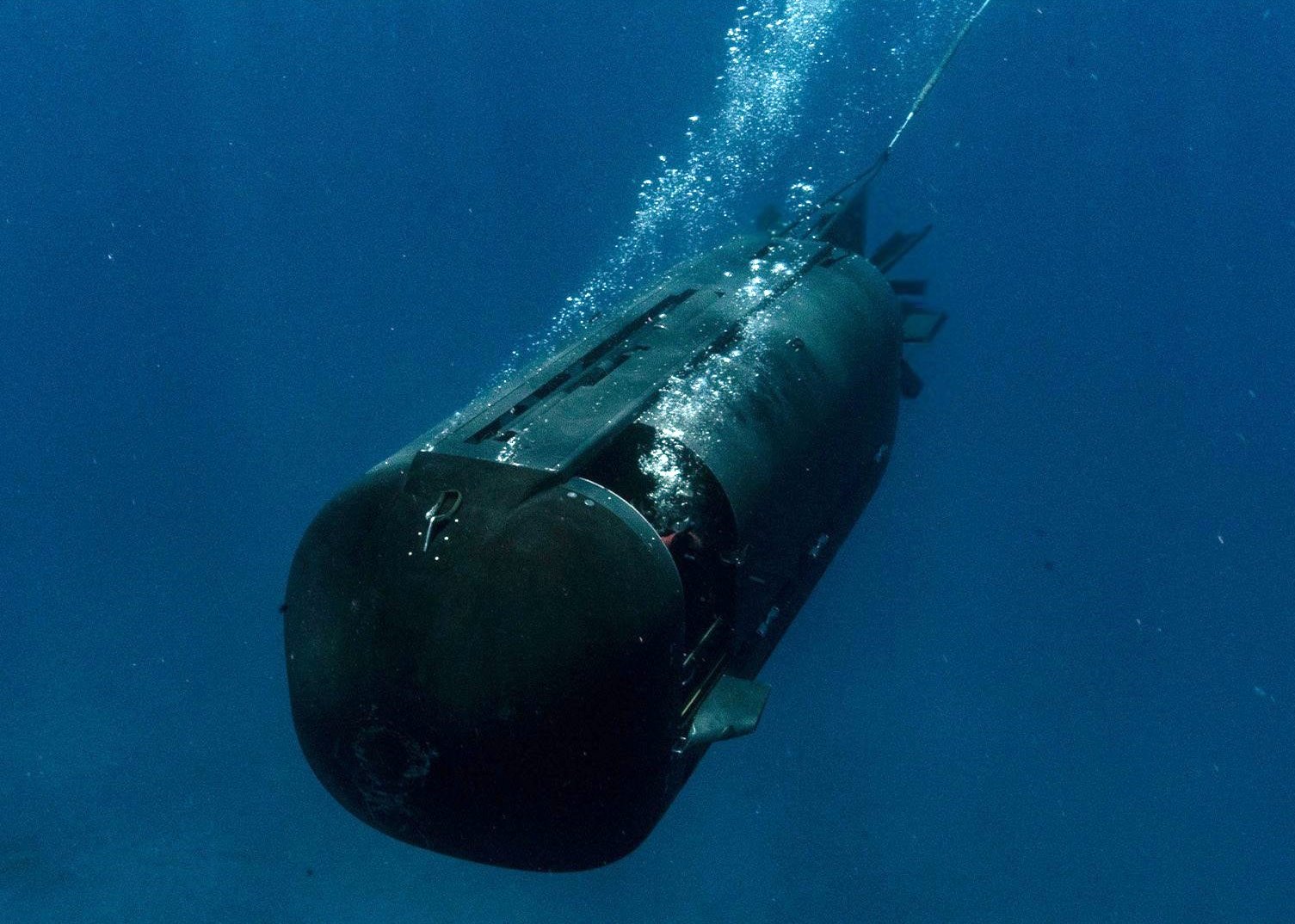

MK VIII SDV underway during training operations.

MK VIII SDV underway during training operations.

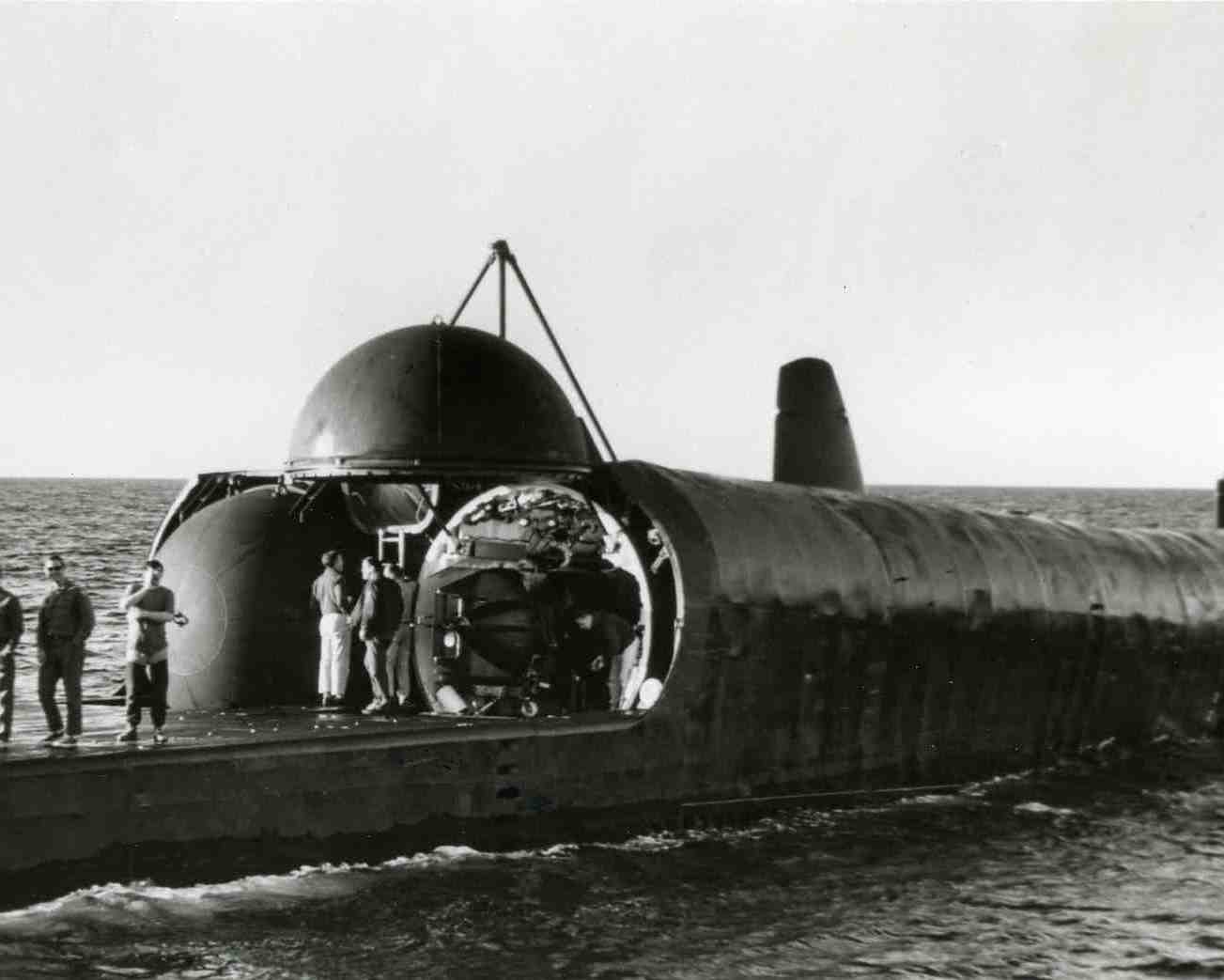

Mk VIII operated by SDV Team ONE during maneuvers into a Dry Deck Shelter fitted to USS Kamehameha (SSN-642). (Photo by Chief Photographer’s Mate Andrew McKaskle)

MK IX SDV pilot and navigator climbing into the boat to begin a training operation. Once in the SDV, the men operated lying in a prone position.